This old ‘House’ a bit shaky as multi-Mitisek ushers in COT regime with goth Philip Glass

“The Fall of the House of Usher,” an opera by Philip Glass and Arthur Yorinks, at Chicago Opera Theater through March 1. ★★★

“The Fall of the House of Usher,” an opera by Philip Glass and Arthur Yorinks, at Chicago Opera Theater through March 1. ★★★

By Nancy Malitz

It remains to be seen whether the new regime at Chicago Opera Theater will succeed in keeping its old audience while striking out in new directions. But Austrian conductor, designer and now general director Andreas Mitisek, who succeeds Brian Dickie after his 13-year regime, is not the sort of leader who wastes time easing in.

The first opera of the company’s 2013 season, and the first under Mitisek’s direction, is a co-production with his other company, Long Beach Opera, of Philip Glass’s 1987 chamber opera “The Fall of the House of Usher.” On paper this looks like a no-brainer: American opera’s most influential composer of the 20th century transforming a gothic horror tale by Edgar Allen Poe, the 19th century’s master of the macabre. You can almost taste the possibilities for sustained tension and terror.

The first opera of the company’s 2013 season, and the first under Mitisek’s direction, is a co-production with his other company, Long Beach Opera, of Philip Glass’s 1987 chamber opera “The Fall of the House of Usher.” On paper this looks like a no-brainer: American opera’s most influential composer of the 20th century transforming a gothic horror tale by Edgar Allen Poe, the 19th century’s master of the macabre. You can almost taste the possibilities for sustained tension and terror.

But Glass and his librettist Arthur Yorinks are mellow to the point of tedium at the opera’s outset. They do pack an eventual wallop as the story picks up steam and we witness Poe’s insane head of the household, Roderick Usher — the last of the male line and living in macabre isolation with his twin sister — succumb to the terror that consumes him. Still, there is little in Glass and Yorink that immediately conveys the delicious sense of dread that Poe puts into our head from his first paragraph, that “iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart … which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime.”

But Glass and his librettist Arthur Yorinks are mellow to the point of tedium at the opera’s outset. They do pack an eventual wallop as the story picks up steam and we witness Poe’s insane head of the household, Roderick Usher — the last of the male line and living in macabre isolation with his twin sister — succumb to the terror that consumes him. Still, there is little in Glass and Yorink that immediately conveys the delicious sense of dread that Poe puts into our head from his first paragraph, that “iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart … which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime.”

Thus this work of big ambition requiring only chamber forces — five singers, a dozen or so musicians — needs a deft and clever hand in staging it to avoid sinking early into a hypnotic lull. Chicago Opera Theater’s production, conceived by Ken Cazan, is perhaps too clever, though, and thereby hangs this twice twisted tale.

Poe’s narrator is the visitor, who has been mysteriously summoned, recalling, “What was it that so unnerved me in the contemplation of the House of Usher? I reined my horse to the precipitous brink of a black and lurid tarn … and gazed down — but with a shudder.” And there you go, typical Poe, straight into vague but hideous fears and irredeemable gloom.

The Yorinks-Glass way into this tale is, by contrast, via a message that the visitor receives in his own abode, and from there a journey, by extended traveling arpeggios, to Roderick’s home.

While music and libretto took their time catching wind, I welcomed Cazan’s drolly contemporary Grand Guignol take on the proceedings, youthful and menacing from the outset, compliments of costume designer Jacqueline Saint Anne and set designer Alan E. Muraoka. Passive-aggressive goth mignons in black leather facilitated the visit to Usher by his childhood friend. (He’s William in this opera. Poe never names him.)

While music and libretto took their time catching wind, I welcomed Cazan’s drolly contemporary Grand Guignol take on the proceedings, youthful and menacing from the outset, compliments of costume designer Jacqueline Saint Anne and set designer Alan E. Muraoka. Passive-aggressive goth mignons in black leather facilitated the visit to Usher by his childhood friend. (He’s William in this opera. Poe never names him.)

It was amusing to find oneself in a creepy dream state where airline stewards have mohawks and ghosts wear platform shoes. The supernumeraries breathed maddening life into the mansion itself, moving its walls and shape-shifting the furniture of this Caligari-like realm. Glass vitrines that look like they might have been plucked from a Roche Bobois catalog double as the bizarre Usher mansion’s beds, tables … coffins. Lighting designer David Martin Jacques’s murky corners and jagged shadows are also disorienting, in just the right way.

Poe leaves it to the reader to sort out the exact nature of Roderick Usher’s torment, though the suggestion of incestuous lust for his sister Madeline and his murderous suppression of same is without question a possibility along with other unnamed sources of terror. Some of Glass’s most glorious music is for the sister, Madeline, to be sung in wordless melismas of longing, and soprano Suzan Hanson, who has had this role in her blood since the opera’s early performances, is dangerously mysterious.

Poe leaves it to the reader to sort out the exact nature of Roderick Usher’s torment, though the suggestion of incestuous lust for his sister Madeline and his murderous suppression of same is without question a possibility along with other unnamed sources of terror. Some of Glass’s most glorious music is for the sister, Madeline, to be sung in wordless melismas of longing, and soprano Suzan Hanson, who has had this role in her blood since the opera’s early performances, is dangerously mysterious.

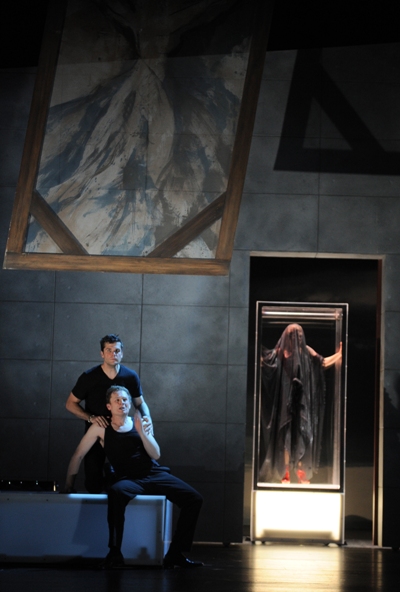

For this COT production, Cazan takes a somewhat different route to Roderick’s psychic disintegration, implying that Madeline may be the personification of Roderick’s suppressed true self, and that she is constantly clawing at him from within, fighting murderously with him, refusing to stay contained any longer.

I think it’s scary and it works before it becomes too explicit. I remain unconvinced by the more overt homosexual attachment that Cazan pursues beyond that — a love story between childhood friends Usher and William that zooms in fairly late on a mutual grope, when all indications are that the opera wants to zoom out toward the House of Usher’s all-encompassing final doom. There are times when unspeakable horror is diminished, even distracted, by specifics and this is one of them.

I think it’s scary and it works before it becomes too explicit. I remain unconvinced by the more overt homosexual attachment that Cazan pursues beyond that — a love story between childhood friends Usher and William that zooms in fairly late on a mutual grope, when all indications are that the opera wants to zoom out toward the House of Usher’s all-encompassing final doom. There are times when unspeakable horror is diminished, even distracted, by specifics and this is one of them.

So the production lost its way. Still, it’s a spunky artistic team that Mitisek assembled — himself a multiple threat who spent the night in the opera pit, conducting, with one broken leg in a splint.

COT followers may wonder whether Mitisek will be able to match Dickie’s outstanding record for securing first-rate singers, and in this production at least, the line-up is very good, above all the mesmerizing Hanson, surely grande dame of Madelines.

The men she tortures psychologically — tenor Ryan MacPherson as the distraught Roderick Usher and baritone Lee Gregory as the uneasy visitor — are distinctive character actors with persuasive, strong and beautiful voices who play off each other well. I wasn’t surprised to see a Richard Nixon (from “Nixon in China”) in Gregory’s resume, nor an Alfred (from “Die Fledermaus”) in MacPherson’s.

Tenor Jonathan Mack (Usher’s physician) and bass-baritone Nick Shelton (Usher’s servant) round out the able cast and crew that’s strong in West Coast ties. The potential for a lively Third Coast-West Coast synergy is quite intriguing, especially if Mitisek proves able to make it work well in both directions.

Related Links:

- Performance location, dates and times: Visit chicagooperatheater.org

- Read the story as Poe wrote it: Go to gutenberg.org

- Check out Mitisek’s other opera company: Go to longbeachopera.org

Photo captions and credits: Home page and top: Roderick Usher (Ryan MacPherson) is obsessed by the death of his sister in Philip Glass’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Descending: COT general director Andreas Mitisek conducts these performances. Madeline (Suzan Hanson) and brother Roderick (Ryan MacPherson) have a fraught relationship. YouTube excerpts from the COT production. Supernumeraries are gothic punks in the conception of director Ken Cazan and designer Alan E. Muraoka. Madeline (Suzan Hanson) and brother Roderick (Ryan MacPherson) may be aspects of the same person as interpreted by director Ken Cazan. Seated Roderick (Ryan MacPherson) is drawn to William (Lee Gregory) and tormented by his sister Madeline (Suzan Hanson) in Cazan’s interpretation. Below: The mansion seems alive, with many moving parts. (COT production photos by Liz Lauren)

Tags: Alan E. Muraoka, Andreas Mitisek, Arthur Yorinks, Chicago Opera Theater, David Martin Jacques, Jacqueline Saint Anne, Jonathan Mack, Ken Cazan, Lee Gregory, Liz Lauren, Long Beach Opera, Nancy Malitz, Nick Shelton, Philip Glass, Ryan MacPherson, Suzan Hanson, The Fall of the House of Usher